What To Do If You Fall In Love With An Anime Character

Can You lot Actually Fall In Love With a Fictional Graphic symbol?

The word "beloved" has a variety of meanings. A person can say "I love my mom," "I love my sis," "I love my fiancé," and "I beloved my cat" and mean something different each time. Merriam-Webster also has a separate definition for affection for impersonal things like music, food, or favorite places to be.

Fans of fiction (including books, movies, television shows, etc.) take that concluding definition even farther. They say "I love Kaylee Frye (from Firefly and Tranquility )," "I beloved Mr. Darcy (from Pride & Prejudice) ," or "I honey Hiccup (from How to Train Your Dragon 2 )." These fictional characters are technically impersonal things considering they are only ideas, only people'southward affections for them can experience very personal. Is this an impersonal love? Is information technology whatsoever different from beloved for the story? If it can't be reciprocated, can it exist anything like the "real" love people experience for family, friends, and meaning others? And what would the implications be if it were real?

How Many Means to Say I Love Y'all?

To determine if honey for fictional characters can be real, it helps to determine what "love" means. The Greeks went even further than Merriam-Webster. They had at least 7 unlike words that interpret to love in English, each with different applications.

Philautia is self-love; that definitely does non apply to beloved between real people and fictional characters.Pragma is love based on reason and external factors like arranged marriages or public appearances. Real people aren't put in arranged relationships with fictional characters, so that term is out, too. Ludus is the version of love people experience in "no strings attached" relationships. Every bit Psychology Today puts information technology, "ludus works all-time when both parties are self-sufficient." Fictional characters practise not meet that criterion (they are dependent on writers for their being), so their real-world lovers probably don't feel ludus.

Eros is close enough to ludus that the latter is sometimes mistaken for the former. It is the Greek term for concrete attraction that drives people to make love and sometimes more eccentric demonstrations of their passion.

When fans speak of their love for fictional characters, a mutual assumption is they are physically attracted to the actors portraying them in movies or goggle box shows. Information technology's non Sherlock Holmes, Loki, and the Doctor they love, for example, simply Benedict Cumberbatch, Tom Hiddleston, and David Tennant.

Even when the character originally comes from a book, if an adaptation exists, that is the version that appears in the posters and life-size paper-thin cutouts. Thus, say the observers, fans experience eros for the actors, not the characters.Still, some fans describe feeling physically attracted to animated characters. The voices provided past real people may be function of the reason, only they cannot business relationship for all of the flattering fan art.

Which characters become the objects of a fan's eros is largely determined past subjective sense of taste, just like who finds whom attractive in real life. However, a grapheme can be bandage, costumed, and/or animated in specific ways to elicit concrete attraction. This is sometimes chosen fan service. It draws attending to the shallowness of eros and calls into question how genuine this kind of dear is.

Philia is also known every bit platonic friend-honey. Eros is physical animalism, whereas philia is a want for agreement. Equally Aristotle described it, philia is based on the conventionalities that the one you lot love is useful, likable, or virtuous.Real people can seek to ameliorate understand their favorite fictional characters by reading more, watching more, or coming up with their own ideas. Authors and show-runners requite their characters development for that very purpose.

As Aristotle described it, philia is based on the conventionalities that the person you beloved is useful, likable, or virtuous. This description is especially appropriate considering fictional characters often have many distinct qualities worthy of ideal adoration. In a similar fashion, fans say they hate the characters they detect distinctly not-virtuous or unlikable. If a fan's significant other is calumniating or otherwise unpleasant, that fan may be particularly drawn to heroes with kind hearts. This state of affairs and many others like it are philia at work.

Storge is familial love. People develop it for other existent people through familiarity; young children learn to dear their families not considering of physical attraction (despite what Freud might say), only because they grow upwardly together. Adoration (philia) is often office of information technology, just information technology unremarkably comes after storge.Fans may develop storge for fictional characters that they "grew upwards with" or otherwise spent a lot of time reading about or watching. Psychology Today points out that storge can exist "unilateral or asymmetrical," so it seems a practiced fit for what fans call dearest of characters that cannot reciprocate.

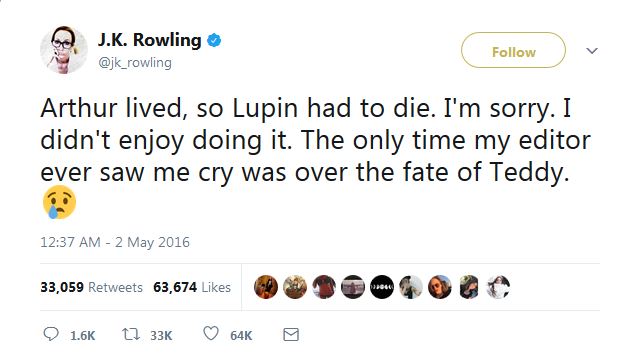

Storge is virtually relevant when a character dies or otherwise leaves the story. Fans may feel levels of loss "normally" reserved for family members and very close friends. Authors even have this feeling for characters they create; J.K. Rowling has admitted to crying when she found herself forced to kill her characters in the Harry Potter serial.

Last but not least, agape is the discussion for the donating or selfless love people have for strangers. Not anybody embodies agape for their fellow non-fictional people, but fans may feel a genuine want for their favorite fictional characters' best interests. If it is honey, information technology is indeed a selfless love, every bit the object of the fans' affection cannot do anything in return.

Again, which fictional characters receive agape is up to the individual fan. The seemingly random connection some fans feel for short-lived characters in horror stories may not experience similar love, but it is technically afraid. Maybe it is the relatable characters or simply the tragic, sympathetic ones we develop this donating love for. Some fans develop agape for fictional characters specifically because they enjoy the story containing those characters; perhaps information technology's a chicken-egg question of which affectionate feelings came first.

So there are four possible meanings for a fan maxim "I love Aladdin." Information technology could hateful "I am physically attracted to this cartoon drawing" (Eros), "I discover this person likable and virtuous and I want to learn more well-nigh him" (Philia), "I have developed a fondness for this person over the years" (Storge), or "I take altruistic business for the best interests of this person" (Agape). Most likely it is some combination of these feelings. It seems there is much more to be explored simply in defining what love means in this context, not fifty-fifty considering the implications.

If Loving You is Wrong…

The author of "Ask Anne" says this about feeling love for fictional characters: "People do this all the fourth dimension. Dearest at offset sight is love of the visual advent of a person combined with honey of a fiction." This is what makes eros work in full general.This fact tin lessen the business organisation that fictional characters cannot render the angel of their fans. Information technology should be no more than concerning than a celebrity vanquish. Affection for real-life famous people is based on their visual appearance (eros) and what fans imagine their personalities to be. The simply difference with fictional characters is fans are told what to imagine about their personalities past the writers and sometimes the actors backside the characters.

As Anne goes on to say, affection for fictional characters becomes problematic when nosotros prefer our called fiction to relationships with real people. It seems similar to the problem with pornography; porn is fabricated specifically for people to feel eros for a fantasy, a fictitious person, and those who fall for its attraction run the risk of dampening their affection for real people. It is easier to avert this danger with movies and television shows that aren't porn, but fans should however beware that their reason for "loving" a fictional character may actually exist lust.In this way, feelings of eros for fictional characters can put strain on romantic relationships between real people. A fan may develop unreasonable standards for their real-life significant other, hoping he/she will look or human action more like the object of a fictional crush. These fans may struggle to keep or find pregnant others. Feelings of storge for fictional characters may lead to a similar problem; fans risk losing affection for the real people they should feel familiarity and love for.

The good news is, despite the worries of many fans, there does not seem to be evidence that feeling overly attached to fictional characters is a sign of a mental disorder (assuming fans understand that fictional characters are, in fact, fictional). If it were a symptom of something, it would be peculiarly hard to terminate, and real-life relationships would be in big problem. But fans tin can rest easy knowing that affection for characters will not irrevocably impairment their ability to feel things for real people.

Meanwhile, agape and philia are actually admirable in this circumstance. Caring for a character's best interests and wanting to learn more virtually them tin be constructive. This is good practise for empathy. For example, authors oftentimes brand the beloved interests of their protagonists and narrators attractive, cartoon attention to their admirable characteristics to brand it clear why the main characters are falling in love with them. When fans experience similar amore for these characters, they can empathize.

Some people struggle with connecting to people and empathy in general. Well-told stories assistance fans empathise and connect with characters through means other than familiarity and attraction to visual advent. This can be surprisingly helpful for people with "emotional deficits." The boosted advantage of practicing emotional connection on fictional characters is there are less strings fastened. Equally Will Grayson said in the John Green/David Levithan novel Will Grayson, Will Grayson , "You like someone who tin't similar you back because unrequited love can be survived in a way that one time-requited love cannot." Over again, every bit long equally the fans empathise that their fictional crushes are fictional, they won't be badly hurt when zero comes of these feelings.

Many existent-life relationships start with attraction to concrete apperance (eros). Over time, hopefully, the lover will develop philia (adoration for the other person'south skillful qualities) and afraid (selfless caring for their well-existence). Information technology is certainly possible to feel these kinds of love for fictional characters. These pseudo-relationships tin can become addicted memories when fans move on to a real-life love story. And the characters volition always be in that location when they need them.

What do y'all call back? Leave a comment.

Receive our weekly newsletter:

Source: https://the-artifice.com/love-fictional-character/

Posted by: jorgensenbouselt.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What To Do If You Fall In Love With An Anime Character"

Post a Comment